文/何明諠(台灣人權促進會專員)

今年(2016)3/30至4/1,台權會「網路自由與隱私」專員何明諠,前往舊金山的矽谷參加 RightsCon 會議,與韓國、香港的與會者,分別報告台灣、香港、韓國民間團體及學術單位所做的「網路透明報告」成果。另外,也有美國的與會者報告他們所做的企業「網路透明報告」成果。 長期關注「網路自由與數位人權」的全球性組織 Access Now,也撰文介紹台灣、韓國、香港的「網路透明報告」。 底下為全文:

Don’t take their word for it: scrutinizing government transparency reports

This is the second of a two-part series of posts on transparency reports. The first analyzed findings from our newly updated Transparency Reporting Index. In this post, we look at three reports by civil society groups in East Asia — many of which will participate next week at RightsCon Silicon Valley 2016. They report on how well their governments are meeting their responsibility to respect human rights in the digital age.

Transparency reports help investors, board members, civil society groups, and other stakeholders evaluate whether companies are meeting their commitments to be more transparent and accountable. But in a growing trend, governments are also being asked to disclose information and statistics on their requests to access users’ information or restrict content. Public officials and agencies have begun to comply as part of an effort to increase trust among citizens both in and outside their borders. This is a laudable development. However, as we note below, government agencies sometimes report inconsistent or incomplete data, or they refuse to release data even if they are required to do so by law.

Governments self-report that their requests are increasing

A trio of reports from East Asia show that governments are acknowledging that they have increased their requests for access to users’ data and censorship of user-generated content. It’s great to see civil society taking initiative to research and share these numbers for their respective countries, but it would be even better if governments themselves were to share these numbers in an accessible format, without requiring an intricate civil society investigation.

To their credit, the groups issuing these reports provide a model for how other stakeholders worldwide can prod and push public officials to open up about the scope and scale of government surveillance and restrictions of online content.

Civil society in Taiwan uncovers big discrepancies between the government’s reported volume of requests and what companies report

The Taiwan Internet Transparency Report (TITR) is a research project of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights. In 2015, the project was published in English for the first time. The 2015 report indicates that from 2012 to 2014, there were at least 4,908 requests for personal data. Of these, 77% of requests came from the police, which often justified the requests on the grounds that they prevent crime.

The Taiwanese government frequently cited the “Personal Information Protection Act” and the “Freedom of Government Information Law” in its refusal to provide data. However, it eventually gave the required statistics to the TITR. This was a victory for TITR, as the government seemed willing to come up with any excuse to avoid disclosing statistics on government requests, even though no details were requested other than the numbers.

One finding of concern is that the transparency report shows a large gap between the statistics provided by the government and those provided by individual enterprises. The report shows that the government made 4,181 data requests from five companies (Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Google, and Yahoo) in the first half of 2014 alone. However, the government disclosed that its requests for user information totaled only 4,908 requests for all of 2012, 2013, and 2014. The TITR hopes that in the future it can obtain more statistics from local companies to close the gap between the figures provided by government entities and those provided by the large enterprises.

The government also claimed a higher success rate for content-takedown requests than what was provided by the relevant enterprises. Specifically, the government claimed its success rate has increased to 91.5%. However, according to the Google Transparency Report, the success rate ranged from 0-30% throughout 2012, 2013, and 2014. It remains unclear what caused such a large variation. Additionally, it is unclear which authorities have the authority to remove internet content. For example, the human rights organization found that there should be 16 units with such authority. However, there are only six units that replied to the transparency reporting group claiming to have authority for content removal.

There are other discrepancies, as well. For instance, there were no government-reported instances of communication surveillance. However, according to reports by the Judicial Yuan, the highest judicial organ in the Republic of China, there were at least 68 cases in which there was direct communication surveillance related to the internet. Access Now suggests that both the governments and telecommunication companies provide their data for transparency reports as a system of quality control. As is readily apparent, the statistics reported by government and private companies do not always match. It would be beneficial for all parties involved to have both government and private companies provide the data in an easily comparable list of categories.

There are a number of indicators that the TITR project hopes to include in the future surveys, which may be beneficial for others that want to prepare transparency reports. These include providing information regarding government blocking mechanisms; usage of data requests; notification of the parties about the number of requests and types of cases; distinguishing between requests for metadata and content data; disclosing data sharing among government units; disclosing information about data storage; and a list of Internet Service Providers with related statistics from the ISPs, as a means to monitor them and let the people know which ones they can trust.

Search and seizures of Korean communication service providers will continue to be Korea’s Internet Transparency Report’s greatest challenge, as these data are not made readily available by the Korean government

Last fall, the Korea Internet Transparency Report (KITR) launched its comprehensive guide to 2011-2014 Korean internet censorship and surveillance. The group carries out ongoing analysis of the data released by the Korean government while working with officials to make more specific data available. The Korea Internet Transparency Report analyzes the status of the Korean government’s surveillance and censorship on the internet and its problems, and also provides information on prominent individual cases. Additionally, the group assesses areas which it is hopeful to see improvement in the future.

On surveillance, the KITR uses four major indicators to determine the present level of government transparency. They are: interceptions; acquisition of communication metadata; provisions of subscriber identifying information; and search-and-seizure notices for service providers or providers of telecommunications equipment.

In accordance with current law, all Communications Service Providers (CSPs) are required to report to the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Ministry biannually regarding these four major indicators. The ministry then discloses the statistical data based on these reports. Important to note, however, is that Korean law permits search and seizures of CSPs. This procedure allows the government to collect the entire spectrum of data, including the content, metadata, and subscriber identifying information. The government does not include the data on search and seizures in its report to the KITR. However, Naver and Kakao, two major Korean service providers, gave their respective data on search and seizures to the KITR for analysis.

According to Naver and Kakao, each search and seizure request involves information from an average of 68 accounts. This depicts a very de-particularized scope. The report estimates that the information of 1.5 million accounts of internet users and five million general users’ accounts are being provided through the search and seizure authority. Again, this means that the content of the communications from these accounts are provided to the government.

The KITR found that there has been a steep increase in the number of interceptions of email, messenger, and community accounts. This is most likely a reflection of the current transition to online messaging as a means of communication. Some 90% of these interceptions seem to be made for national security-related investigations.

While acquisition of communications metadata and subscriber identifying information is decreasing, two other powerful methods of surveillance — search and seizure requests, and interception — are increasing, and both allow the government to see the contents of a message.

KITR’s frequently updated Case & Issue blog also details specific blocking and content deletion orders issued by the Korea Communications Standards Commission. A February. 2016 post, for example, notes that a Korean court overturned a decision by the KCSC, an administrative body, to block 4shared.com, a storage-locker website where users can upload, store, and download content. The court found that the KCSC, which handles takedown requests for online content, can only lawfully order a takedown if the website is entirely geared towards aiding illegal downloading. The fact that some illegal content was being distributed through the website did not satisfy such a strict standard. The court found that it would be disproportionate to take down the entire site even though some illegal materials could be located on the website, providing a needed check and balance on the power of the administrative agency.

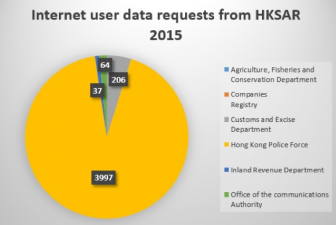

Hong Kong Transparency Report noted a 20% jump in requests from 2014

The Hong Kong Transparency Report for 2015 has not been released yet. However, the group shared an infographic of data that shows a 20% increase in government requests for data from 2014 numbers. The vast majority came from the Hong Kong police force, as the graphic indicates.

The Hong Kong group has not gotten a satisfactory answer for why there has been an 82% increase in requests to Facebook over the first half of 2015 compared to the first half of 2014. The group speculates, however, that police increased social media monitoring during the Occupy movement of Spring 2015.

Continued vigilance in East Asia transparency

It is a great to see civil society groups like the KITR, the Hong Kong Transparency Reporting group, and Taiwan Internet Transparency Report taking advantage of transparency reports from both governments and telecom and internet companies. These transparency reports are helping to keep those who control data in check, while limiting their ability to abuse consumers’ personal data. They are also keeping the public informed. Hopefully, in the future, we will see more consistency in the reported statistics between the government agencies and civil society. We support these groups in their push for more data and more consistent reporting by all stakeholders.

You can visit the Transparency Reporting Index here. You can stay updated on this and other digital rights issues by following us on Twitter, liking us on Facebook, and subscribing to our newsletter and action alerts.