By Citizen Lab and Tibet Action Institute

Tenzin, is a designer who is hard at work updating the website of a Tibetan human rights organization. She receives an email that includes a file attachment from a group of colleagues who have been working with her on the project. At first look it seems like just another one of the mundane emails we receive everyday. But beneath the surface something much more insidious is happening. The email was not sent by her colleague, but by someone pretending to be them. If the attachment was opened it would appear to be the document that was sent, but in the background it would run malware (malicious software) that gives whoever sent the email remote access to the computer and allows them to take files, record keystrokes, and even turn on the webcam and microphone all without any indication that something is wrong. But something is very wrong. Tenzin has been targeted by cyber espionage.

This story actually happened and is not an isolated incident. For many civil society communities around the world being targeted by cyber espionage is a constant reality. The malware used in these operations seeks to collect sensitive data from computers and networks and stay active for as long as possible without being detected. The information that is gathered can lead to real consequences including psychosocial strain and even physical harms such as arrests or detention. Tracing the connection between the compromise of a computer or network to a physical harm can be challenging, because the relationship between the digital compromises and the use of the compromised information by threat actors is indirect. Unlike the consequences of physical threats, which are often readily observable, the most serious impacts of digital threats are typically at least one step removed from the technology that has been exploited. Despite these challenges, harms connected to targeted malware have been documented across Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America. Cyber espionage capabilities are accessible to both state and non-state actors, and can infiltrate social movements with nothing more than a carefully crafted email and a couple clicks.

The Tibetan community has been persistently targeted by cyber espionage for over a decade. Understanding the information security threats that Tibetans have weathered over these years shines a light onto a practice that hides in the shadows. In reaction to these threats, Tibetans are working to educate themselves on information security and develop strategies for keeping their community safe. In this article, we provide an overview of recent research into cyber espionage operations against the Tibetan community and the efforts Tibetans have made to empower and protect themselves. These experiences are instructive for other diaspora communities and civil society movements in Asia and around the world who may face similar challenges.

A street scene in Dharamsala, India home to the world’s largest population of Tibetan refugees (photo credit: Nick de Pencier)

Malware Campaigns and China

Public reports on malware campaigns originating from or related to China began to emerge in the early 2000s. In the past five years, the number of reports on these activities have steadily grown with high profile compromises documented against governments around the world and a large number of industries, including major companies like Google, RSA, and Boeing. The United States has been particularly vocal on the threat these attacks pose to national security and commerce. The Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property claims intellectual property theft against the US is primarily orchestrated by China through cyber espionage and accounts for losses of up to 300 billion dollars a year. General Keith Alexander, former Director of the National Security Agency and Commander of United States Cyber Command, has called the theft of US intellectual property through cyber espionage the “greatest transfer of wealth in history.”

In 2009, the Citizen Lab released one of the first public reports that revealed a cyber espionage network that we called GhostNet.This investigation began through field work conducted by Greg Walton who worked with Tibetan organizations in northern India including the Offices of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the Central Tibetan Administration, and several Tibetan NGOs. These organizations had concerns regarding their information security, and, with their consent, we collected data from their networks to investigate. What we found was astounding. Through technical analysis led by Nart Villeneuve, we uncovered a cyber espionage network that had compromised over 1,295 infected computers in 103 countries including a number of high profile targets such as the Offices of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and other prominent organizations from the Tibetan community as well as embassies and foreign ministries of numerous countries. The operators of GhostNet gained access to these computers and networks by sending emails with malware-laden attachments and messages that convinced their targets to open the malicious files.

Our investigation found that the servers that acted as the machines that command and control the infected computers were physically based in Hainan, China. However, we were not able to conclusively determine who was sponsoring or operating GhostNet.

While we do not know who was ultimately behind GhostNet, knowing who its victims were confirmed that the Tibetan community, alongside prominent government institutions, are systematically targeted by cyber espionage campaigns that appear to have political motivations.

Claims of attribution surrounding these attacks abound, with some researchers making direct connections to the Chinese government and military, and others drawing links to the Chinese hacker underground or technical universities. Conclusive proof that a cyber espionage operation is the work of a state-sponsored actor is often elusive. Regardless of how connected the Chinese government may or may not be to these activities, years of documented cyber espionage operations show that there are well-resourced and persistent threat actors originating from China targeting Tibetans and other civil society communities.

Communities @ Risk

As a follow-up to the GhostNet report, the Citizen Lab (in collaboration with Tibet Action Institute) conducted a study of targeted malware campaigns against ten civil society groups over the course of four years, which we published in a comprehensive report entitled “Communities @ Risk: Targeted Digital Threats Against Civil Society”. The ten participating groups included five Tibetan organizations and three human rights groups generally focused on justice and democracy issues in China. Tracking threats against these groups over an extended period provided unique insights. Below we outline a selection of our findings.

Tibetans are targeted as a community

The Tibetan community and other diasporas function as networks and are targeted as networks. The emails used in malware campaigns against Tibetans are made to appear to come from trusted groups from within the community and reference issues that Tibetans care about. The operators behind the campaigns send out waves of emails to Tibetan journalists, politicians, and activists often in focused bursts around events and anniversaries of importance. It only takes one person in an organization to be compromised for operators to gain a foothold into a network and move laterally through it. From the one compromised organization, operators can collect information for future targets and hop to the next group. Over time, the communications of an entire network and movement can be infiltrated. Civil society must defend itself as a network. Securing one person or organization is not sufficient. Strategies must be adopted to strengthen the community as a whole against these threats.

Civil society groups face the same threats as the private sector and government, while equipped with far fewer resources to secure themselves

The same tactics, tools and procedures used to target the networks of governments and the private sector are being used to target Tibetans and other civil society communities. Unlike governments and private industries, civil society has limited resources and technical capacity, which makes responding to these threats a greater challenge. These limited resources mean that the expensive technical solutions and consulting services that government and private sector typically rely on to deal with cyber espionage are out of reach for civil society. Instead grassroots efforts to inform, educate, and change the behaviours of communities can be effective in mitigating the threats.

Operators constantly adapt their tactics; often in reaction to defensive measures

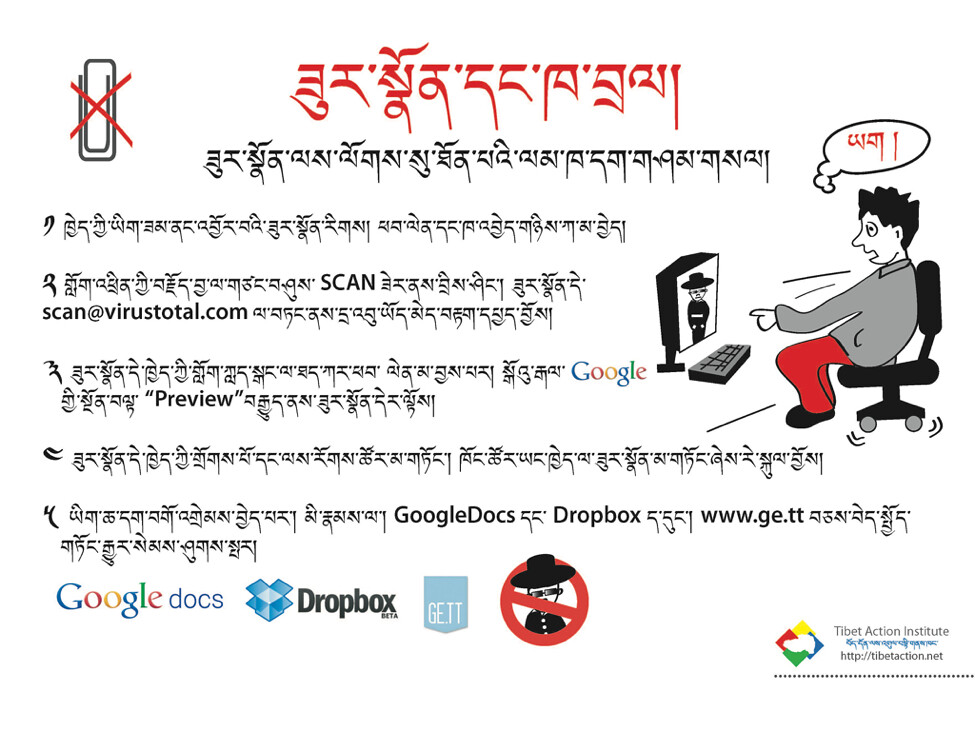

The operators behind cyber espionage campaigns are persistent, patient, and will adapt their tactics often in reaction to changes in the communities they are targeting. We found that malicious file attachments were the most common threat Tibetan organizations in our study received. In fact, for two of the groups, simply not opening email attachments would have prevented over 95 percent of the threats they received. The Tibetan community also recognized this pattern and launched an awareness raising campaign that played on a piece of Buddhist wisdom, “Detach from Attachments”. The message of the campaign is simple: don’t send attachments, don’t open attachments, and consider cloud-based platforms such as Google Drive or Dropbox as an alternative for sharing files.

As the community changed behaviours the malware operators also shifted tactics. Recently, Tibetans have been receiving emails with Google Drive links that connect to malware or phishing pages designed to steal Google credentials. This shift stands in contrast to the previous use of malicious attachments and may be evidence of the malware operators adapting to the behavioral countermeasures promoted by the Detach from Attachments campaign. Security is an iterative process. Civil society communities must be vigilant, nimble, and adaptive.

A flyer from Tibet Action Institute promoting the Detach from Attachments awareness campaign

Empowering Communities

The goal of the Tibetan movement is social change through nonviolent action. Securing communications and information is a necessary means for achieve the wider objectives of the movement. In the face of persistent adversaries and with constrained resources, securing systems and information across the community is a significant challenge. A foundational step towards higher security is greater awareness of the threats. This knowledge can be developed through collaborations between research and advocacy groups and through more strategic solidarity between targeted communities.

Research and Advocacy Empower Each Other

Before a problem can be addressed it needs to be properly diagnosed. Targeted communities need to understand the threats. This knowledge can provide insights into how to better educate and train community members to be aware of the threats and defend against them. At risk communities rarely have the resources and time to do research and often find themselves besieged with malware and other attacks at the most critical periods when their capacities are stretched, such as during sensitive political moments and important advocacy opportunities. Partnerships between researchers and advocacy groups can help bridge these gaps and work to build out greater capacities in the community. Forging these partnerships is not without challenges. Trust is key for achieving successful collaborations. Research and advocacy groups need to understand and appreciate each other’s capabilities, sensitivities, and limitations. Trust building is transactional and takes time. When strong partnerships are in place research and advocacy can empower each other.

The Citizen Lab and Tibet Action Institute have worked closely over many years to document information security threats against the Tibetan community. This partnership has enabled The Citizen Lab to conduct more rigorous research into cyber espionage. The findings of these studies have in turn informed the advocacy work of Tibet Action Institute, which develops curricula and training programs for educating Tibetans on information security. These education efforts need to be based on the current state of threats the community faces to be effective. This knowledge can only be gained through focused research. Our partnership is an example of research and advocacy feeding each other in a complementary cycle. By partnering with researchers, Tibet Action Institute developed better trainings and awareness programs and by partnering with advocates, The Citizen Lab produced stronger research that had greater impacts.

Collaborations between research and advocacy groups is important, but for a community to secure itself greater capacity must be developed within it. A major challenge for the Tibetan movement is technical resources. Most Tibetan groups (especially those operating in India where the majority of Tibetan refugees live) have relatively low levels of technical expertise and rarely have system administrators on staff. Evidence-based education and training programs are needed to address this scarcity. Research and advocacy can be used to encourage and train Tibetans in information security to defend networks and the community as a whole. Raising this overall capacity is vital to ensure that the community can sustainably and effectively stay apace of security threats and develop means for mitigating them

Targeted Communities Empower Each Other

The Tibetan community has had to prioritize information security out of necessity. Few communities have been targeted by cyber espionage for as long as Tibetans have. However, Tibetans are far from the only community facing these challenges. Groups advocating for human rights and democracy in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and across other communities in the Asia Pacific and Southeast Asia are increasingly targeted by cyber espionage campaigns. Beyond Asia, journalists and advocates in countries from Bahrain, Ethiopia, United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Syria, Argentina, Ecuador, and many more are also under threat. Research has shown that the sponsors and operators of these operations often share tactics, techniques, and procedures. It is time for civil society to demonstrate similar coordination and strategies to exchange knowledge and data about threats and share best practices in defending against them. Given the common experience of civil society groups confronting information security challenges, a collective approach may yield greater benefits than attempting to tackle these threats in isolation.

We hope that the experience of the Tibetan community can be used to inform the struggles of other groups who may just be becoming aware of the risk of cyber espionage. Researchers, advocates, and at risk communities need to work together to shine a light into the shadowy world of cyber espionage and empower each other to create a more secure, free, and open Internet that enables movements to create positive social change.